Figure 19.1 Medical personnel are at the front lines of extremely dangerous work. Personal protective clothing is essential for any health worker entering an infection zone. (Credit: Navy Medicine/flickr)

Health and Medicine

Chapter Outline

- 19.1 The Social Construction of Health

- 19.2 Global Health

- 19.3 Health in the United States

- 19.4 Comparative Health and Medicine

- 19.5 Theoretical Perspectives on Health and Medicine

On March 19, 2014 a “mystery” hemorrhagic fever outbreak occurred in Liberia and Sierra Leone. This outbreak was later confirmed to be Ebola, a disease first discovered in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. The 2014-2016 outbreak sickened more than 28,000 people and left more than 11,000 dead (CDC 2020).

For the people in West Africa, the outbreak was personally tragic and terrifying. In much of the rest of the world, the outbreak increased tensions, but did not change anyone’s behavior. Infection of U.S. medical staff (both in West Africa and at home) led to fear and distrust, and restrictions on flights from West Africa was one proposed way to stop the spread of the disease. Ebola first entered the United States via U.S. missionary medical staff who were infected in West Africa and then transported home for treatment. Several other Ebola outbreaks occurred in West Africa in subsequent years, killing thousands of people.

Six years after the massive 2014 epidemic, the people of West Africa faced another disease, but this time they were not alone. The Coronavirus pandemic swept across the globe in a matter of months. While some countries managed the disease far better than others, it affected everyone. Highly industrialized countries, such as China, Italy, and the United States, were early centers of the outbreak. Brazil and India had later increases, as did the U.K. and Russia. Most countries took measures that were considered extreme—closing their borders, forcing schools and businesses to close, transforming their people’s lives. Other nations went further, completely shutting down at the discovery of just a few cases. And some countries had mixed responses, typically resulting in high rates of infection and overwhelming losses of life. In Brazil and the United States, for example, political leaders and large swaths of the populations rejected measures to contain the virus. By the time vaccines became widely available, those two countries had the highest numbers of coronavirus death worldwide.

Did the world learn from the Ebola virus epidemics? Or did only parts of it learn? Prior to the United States facing the worst COVID-19 outbreak in the world, the government shut down travel, as did many countries in Europe. This was certainly an important step, but other measures fell short; conflicting messages about mask wearing and social distancing became political weapons amid the country’s Presidential election, and localized outbreaks and spikes of deaths were continually traced to gatherings that occurred against scientific guidance. Brazil’s president actively disputed medical opinions, rejected any travel or business restrictions, and was in conflict with many people in his own government (even his political allies); with Brazil’s slower pace of vaccination compared to the U.S., it saw a steep increase in cases and deaths just as the United States’ numbers started to decline.

Both those opposed to heavy restrictions and those who used them to fight the disease acknowledge that the impacts went far beyond physical health. Families shattered by the loss of a loved one had to go through the pain without relatives to support them at funerals or other gatherings. Many who recovered from the virus had serious health issues to contend with, while other people who delayed important treatments had larger problems than they normally would have. Fear, isolation, and strained familial relationships led to emotional problems. Many families lost income. Learning was certainly impacted as education practices went through sudden shifts. The true outcomes will likely not be fully understood for years after the pandemic is under control.

So now, after the height of the coronavirus pandemic, what does “health” mean to you? Does your opinion of it differ from your pre-COVID attitudes? Many people who became severely ill or died from COVID had other health issues (known as comorbidities) such as hypertension and obesity. Do you know people whose attitudes about their general health changed? Do you know people who are more or less suspicious of the government, more or less likely to listen to doctors or scientists? What do you think will be the best way to prevent illness and death should another pandemic strike?

Medical sociology is the systematic study of how humans manage issues of health and illness, disease and disorders, and healthcare for both the sick and the healthy. Medical sociologists study the physical, mental, and social components of health and illness. Major topics for medical sociologists include the doctor/patient relationship, the structure and socioeconomics of healthcare, and how culture impacts attitudes toward disease and wellness.

Table of Contents

The Social Construction of Health

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Define the term medical sociology

- Differentiate between the cultural meaning of illness, the social construction of illness, and the social construction of medical knowledge

The social construction of health is a major research topic within medical sociology. At first glance, the concept of a social construction of health does not seem to make sense. After all, if disease is a measurable, physiological problem, then there can be no question of socially constructing disease, right? Well, it’s not that simple. The idea of the social construction of health emphasizes the socio-cultural aspects of the discipline’s approach to physical, objectively definable phenomena.

Sociologists Conrad and Barker (2010) offer a comprehensive framework for understanding the major findings of the last fifty years of development in this concept. Their summary categorizes the findings in the field under three subheadings: the cultural meaning of illness, the social construction of the illness experience, and the social construction of medical knowledge.

The Cultural Meaning of Illness

Many medical sociologists contend that illnesses have both a biological and an experiential component and that these components exist independently of each other. Our culture, not our biology, dictates which illnesses are stigmatized and which are not, which are considered disabilities and which are not, and which are deemed contestable (meaning some medical professionals may find the existence of this ailment questionable) as opposed to definitive (illnesses that are unquestionably recognized in the medical profession) (Conrad and Barker 2010).

For instance, sociologist Erving Goffman (1963) described how social stigmas hinder individuals from fully integrating into society. In essence, Goffman (1963) suggests we might view illness as a stigma that can push others to view the ill in an undesirable manner. The stigmatization of illness often has the greatest effect on the patient and the kind of care they receive. Many contend that our society and even our healthcare institutions discriminate against certain diseases—like mental disorders, AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, and skin disorders (Sartorius 2007). Facilities for these diseases may be sub-par; they may be segregated from other healthcare areas or relegated to a poorer environment. The stigma may keep people from seeking help for their illness, making it worse than it needs to be.

Contested illnesses are those that are questioned or questionable by some medical professionals. Disorders like fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome may be either true illnesses or only in the patients’ heads, depending on the opinion of the medical professional. This dynamic can affect how a patient seeks treatment and what kind of treatment they receive.

The Social Construction of the Illness Experience

The idea of the social construction of the illness experience is based on the concept of reality as a social construction. In other words, there is no objective reality; there are only our own perceptions of it. The social construction of the illness experience deals with such issues as the way some patients control the manner in which they reveal their diseases and the lifestyle adaptations patients develop to cope with their illnesses.

In terms of constructing the illness experience, culture and individual personality both play a significant role. For some people, a long-term illness can have the effect of making their world smaller, more defined by the illness than anything else. For others, illness can be a chance for discovery, for re-imaging a new self (Conrad and Barker 2007). Culture plays a huge role in how an individual experiences illness. Widespread diseases like AIDS or breast cancer have specific cultural markers that have changed over the years and that govern how individuals—and society—view them.

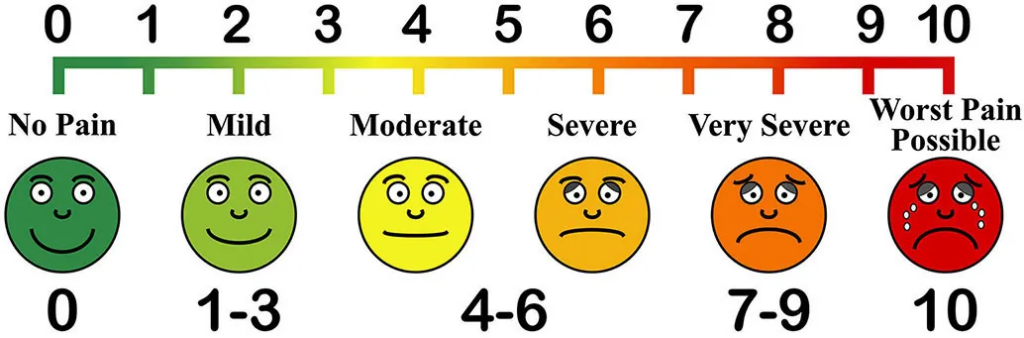

Today, many institutions of wellness acknowledge the degree to which individual perceptions shape the nature of health and illness. Regarding physical activity, for instance, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that individuals use a standard level of exertion to assess their physical activity. This Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) gives a more complete view of an individual’s actual exertion level, since heartrate or pulse measurements may be affected by medication or other issues (Centers for Disease Control 2011a). Similarly, many medical professionals use a comparable scale for perceived pain to help determine pain management strategies.

Figure 19.2 PAIN ASSESSMENT TOOL. The Mosby pain rating scale helps health care providers assess an individual’s level of pain. What might a symbolic interactionist observe about this method? (Credit: Arvin61r58/openclipart)

The Social Construction of Medical Knowledge

Conrad and Barker show how medical knowledge is socially constructed; that is, it can both reflect and reproduce inequalities in gender, class, race, and ethnicity. Conrad and Barker (2011) use the example of the social construction of women’s health and how medical knowledge has changed significantly in the course of a few generations. For instance, in the early nineteenth century, pregnant women were discouraged from driving or dancing for fear of harming the unborn child, much as they are discouraged, with more valid reason, from smoking or drinking alcohol today.

SOCIAL POLICY AND DEBATE

Has Breast Cancer Awareness Gone Too Far?

Figure 19.3 Pink ribbons are a ubiquitous reminder of breast cancer. But do pink ribbon chocolates do anything to eradicate the disease? (Credit: wishuponacupcake/Wikimedia Commons)

Every October, the world turns pink. Football and baseball players wear pink accessories. Skyscrapers and large public buildings are lit with pink lights at night. Shoppers can choose from a huge array of pink products. In 2014, people wanting to support the fight against breast cancer could purchase any of the following pink products: KitchenAid mixers, Master Lock padlocks and bike chains, Wilson tennis rackets, Fiat cars, and Smith & Wesson handguns. You read that correctly. The goal of all these pink products is to raise awareness and money for breast cancer. However, the relentless creep of pink has many people wondering if the pink marketing juggernaut has gone too far.

Pink has been associated with breast cancer since 1991, when the Susan G. Komen Foundation handed out pink ribbons at its 1991 Race for the Cure event. Since then, the pink ribbon has appeared on countless products, and then by extension, the color pink has come to represent support for a cure of the disease. No one can argue about the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s mission—to find a cure for breast cancer—or the fact that the group has raised millions of dollars for research and care. However, some people question if, or how much, all these products really help in the fight against breast cancer (Begos 2011).

The advocacy group Breast Cancer Action (BCA) position themselves as watchdogs of other agencies fighting breast cancer. They accept no funding from entities, like those in the pharmaceutical industry, with potential profit connections to this health industry. They’ve developed a trademarked “Think Before You Pink” campaign to provoke consumer questioning of the end contributions made to breast cancer by companies hawking pink wares. They do not advise against “pink” purchases; they just want consumers to be informed about how much money is involved, where it comes from, and where it will go. For instance, what percentage of each purchase goes to breast cancer causes? BCA does not judge how much is enough, but it informs customers and then encourages them to consider whether they feel the amount is enough (Think Before You Pink 2012).

BCA also suggests that consumers make sure that the product they are buying does not actually contribute to breast cancer, a phenomenon they call “pinkwashing.” This issue made national headlines in 2010, when the Susan G. Komen Foundation partnered with Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) on a promotion called “Buckets for the Cure.” For every bucket of grilled or regular fried chicken, KFC would donate fifty cents to the Komen Foundation, with the goal of reaching 8 million dollars: the largest single donation received by the foundation. However, some critics saw the partnership as an unholy alliance. Higher body fat and eating fatty foods has been linked to increased cancer risks, and detractors, including BCA, called the Komen Foundation out on this apparent contradiction of goals. Komen’s response was that the program did a great deal to raise awareness in low-income communities, where Komen previously had little outreach (Hutchison 2010).

What do you think? Are fundraising and awareness important enough to trump issues of health? What other examples of “pinkwashing” can you think of?

Global Health

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Define social epidemiology

- Apply theories of social epidemiology to an understanding of global health issues

- Differentiate high-income and low-income nations

Social epidemiology is the study of the causes and distribution of diseases. Social epidemiology can reveal how social problems are connected to the health of different populations. These epidemiological studies show that the health problems of high-income nations differ from those of low-income nations, but also that diseases and their diagnosis are changing. Cardiovascular disease, for example, is now the both most prevalent disease and the disease most likely to be fatal in lower-income countries. And globally, 70 percent of cardiovascular disease cases and deaths are due to modifiable risks (Dagenais 2019).

Some theorists differentiate among three types of countries: core nations, semi-peripheral nations, and peripheral nations. Core nations are those that we think of as highly developed or industrialized, semi-peripheral nations are those that are often called developing or newly industrialized, and peripheral nations are those that are relatively undeveloped. While the most pervasive issue in the U.S. healthcare system is affordable access to healthcare, other core countries have different issues, and semi-peripheral and peripheral nations are faced with a host of additional concerns. Reviewing the status of global health offers insight into the various ways that politics and wealth shape access to healthcare, and it shows which populations are most affected by health disparities.

Health in High-Income Nations

Obesity, which is on the rise in high-income nations, has been linked to many diseases, including cardiovascular problems, musculoskeletal problems, diabetes, and respiratory issues. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2011), obesity rates are rising in all countries, with the greatest gains being made in the highest-income countries. The United States has the highest obesity rate at 42 percent; some of these people are considered severely obese, which occurs in 9 percent of U.S. adults (Hales 2020).

Wallace Huffman and his fellow researchers (2006) contend that several factors are contributing to the rise in obesity in developed countries:

- Improvements in technology and reduced family size have led to a reduction of work to be done in household production.

- Unhealthy market goods, including processed foods, sweetened drinks, and sweet and salty snacks are replacing home-produced goods.

- Leisure activities are growing more sedentary, for example, computer games, web surfing, and television viewing.

- More workers are shifting from active work (agriculture and manufacturing) to service industries.

- Increased access to passive transportation has led to more driving and less walking.

Obesity and weight issues have significant societal costs, including lower life expectancies and higher shared healthcare costs.

While ischemic heart disease is the single most prevalent cause of death in higher-income countries, cancers of all types combine to be a higher overall cause of death. Cancer accounts for twice as many deaths as cardiovascular disease in higher-income countries (Mahase 2019).

Health in Low-Income Nations

In peripheral nations with low per capita income, it is not the cost of healthcare that is the most pressing concern. Rather, low-income countries must manage such problems as infectious disease, high infant mortality rates, scarce medical personnel, and inadequate water and sewer systems. Due to such health concerns, low-income nations have higher rates of infant mortality and lower average life spans.

One of the biggest contributors to medical issues in low-income countries is the lack of access to clean water and basic sanitation resources. According to a 2014 UNICEF report, almost half of the developing world’s population lacks improved sanitation facilities. The World Health Organization (WHO) tracks health-related data for 193 countries, and organizes them by region. In their 2011 World Health Statistics report, they document the following statistics:

- Globally in 2019, the rate of mortality for children under five was 38 per 1,000 live births, which is a dramatic change from previous decades. (In 1990, the rate was 93 deaths per 1,000 births (World Health Organization 2020.)) In low-income countries, however, that rate is much higher. The child mortality rate in low-income nations was 11 times higher than that of high-income countries—76 deaths per 1,000 births compared to 7 deaths per 1,000 births (Keck 2020). To consider it regionally, the highest under-five mortality rate remains in the WHO African Region (74 per 1000 live births), around 9 times higher than that in the WHO European Region (8 per 1000 live births) (World Health Organization 2021).

- The most frequent causes of death in children under five years old are pneumonia, diarrhea, congenital anomalies, preterm birth complications, birth asphyxia/trauma, and malaria, all of which can be prevented or treated with affordable interventions including immunization, adequate nutrition, safe water and food and quality care by a trained health provider when needed.

The availability of doctors and nurses in low-income countries is one-tenth that of nations with a high income. Challenges in access to medical education and access to patients exacerbate this issue for would-be medical professionals in low-income countries (World Health Organization 2011).

Health in the United States

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Apply social epidemiology to health in the United States

- Explain disparities of health based on gender, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity

- Summarize mental health and disability issues in the United States

- Explain the terms stigma and medicalization

Health in the United States is a complex and often contradictory issue. On the one hand, as one of the wealthiest nations, the United States fares well in health comparisons with the rest of the world. However, the United States also lags behind almost every industrialized country in terms of providing care to all its citizens. The following sections look at different aspects of health in the United States.

Health by Race and Ethnicity

When looking at the social epidemiology of the United States, it is hard to miss the disparities among races. The discrepancy between Black and White Americans shows the gap clearly; in 2018, the average life expectancy for White males was approximately five years longer than for Black males: 78.8 compared to 74.7 (Wamsley 2021). (Note that in 2020 life expectancies of all races declined further, though the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic was a significant cause.) Other indicates show a similar disparity. The 2018 infant mortality rates for different races and ethnicities are as follows:

- Non-Hispanic Black people: 10.8

- Native Hawaiian people or other Pacific Islanders: 9.4

- Native American/Alaska Native people: 8.2

- Hispanic people: 4.9

- Non-Hispanic White people: 4.6

- Asian and Asian American people: 3.6 (Centers for Disease Control 2021)

According to a report from the Henry J. Kaiser Foundation (2007), African Americans also have higher incidence of several diseases and causes of mortality, from cancer to heart disease to diabetes. In a similar vein, it is important to note that ethnic minorities, including Mexican Americans and Native Americans, also have higher rates of these diseases and causes of mortality than White people.

Lisa Berkman (2009) notes that this gap started to narrow during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, but it began widening again in the early 1980s. What accounts for these perpetual disparities in health among different ethnic groups? Much of the answer lies in the level of healthcare that these groups receive. The National Healthcare Disparities Report shows that even after adjusting for insurance differences, racial and ethnic minority groups receive poorer quality of care and less access to care than dominant groups. The Report identified these racial inequalities in care:

- Black people, Native Americans, and Alaska Native people received worse care than Whites for about 40 percent of quality measures.

- Hispanic people, Native Hawaiian people, and Pacific Islanders received worse care than White people for more than 30 percent of quality measures.

- Asian people received worse care than White people for nearly 30 percent of quality measures but better care for nearly 30 percent of quality measures (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2020).

Health by Socioeconomic Status

Discussions of health by race and ethnicity often overlap with discussions of health by socioeconomic status, since the two concepts are intertwined in the United States. As the Agency for Health Research and Quality (2010) notes, “racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to be poor or near poor,” so much of the data pertaining to subordinate groups is also likely to be pertinent to low socioeconomic groups. Marilyn Winkleby and her research associates (1992) state that “one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of a person’s morbidity and mortality experience is that person’s socioeconomic status (SES). This finding persists across all diseases with few exceptions, continues throughout the entire lifespan, and extends across numerous risk factors for disease.” Morbidity is the incidence of disease.

It is important to remember that economics are only part of the SES picture; research suggests that education also plays an important role. Phelan and Link (2003) note that many behavior-influenced diseases like lung cancer (from smoking), coronary artery disease (from poor eating and exercise habits), and AIDS initially were widespread across SES groups. However, once information linking habits to disease was disseminated, these diseases decreased in high SES groups and increased in low SES groups. This illustrates the important role of education initiatives regarding a given disease, as well as possible inequalities in how those initiatives effectively reach different SES groups.

Health by Gender

Women are affected adversely both by unequal access to and institutionalized sexism in the healthcare industry. According to a recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation, women experienced a decline in their ability to see needed specialists between 2001 and 2008. In 2008, one quarter of women questioned the quality of their healthcare (Ranji and Salganico 2011). Quality is partially indicated by access and cost. In 2018, roughly one in four (26%) women—compared to one in five (19%) men—reported delaying healthcare or letting conditions go untreated due to cost. Because of costs, approximately one in five women postponed preventive care, skipped a recommended test or treatment, or reduced their use of medication due to cost (Kaiser Family Foundation 2018).

We can see an example of institutionalized sexism in the way that women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with certain kinds of mental disorders. Psychologist Dana Becker notes that 75 percent of all diagnoses of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) are for women according to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. This diagnosis is characterized by instability of identity, of mood, and of behavior, and Becker argues that it has been used as a catch-all diagnosis for too many women. She further decries the pejorative connotation of the diagnosis, saying that it predisposes many people, both within and outside of the profession of psychotherapy, against women who have been so diagnosed (Becker).

Many critics also point to the medicalization of women’s issues as an example of institutionalized sexism. Medicalization refers to the process by which previously normal aspects of life are redefined as deviant and needing medical attention to remedy. Historically and contemporaneously, many aspects of women’s lives have been medicalized, including menstruation, premenstrual syndrome, pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause. The medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth has been particularly contentious in recent decades, with many women opting against the medical process and choosing a more natural childbirth. Fox and Worts (1999) find that all women experience pain and anxiety during the birth process, but that social support relieves both as effectively as medical support. In other words, medical interventions are no more effective than social ones at helping with the difficulties of pain and childbirth. Fox and Worts further found that women with supportive partners ended up with less medical intervention and fewer cases of postpartum depression. Of course, access to quality birth care outside the standard medical models may not be readily available to women of all social classes.

SOCIOLOGY IN THE REAL WORLD

Medicalization of Sleeplessness

Figure 19.4 Many people fail to get enough sleep. But is insomnia a disease that should be cured with medication? (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

How is your “sleep hygiene?” Sleep hygiene refers to the lifestyle and sleep habits that contribute to sleeplessness. Bad habits that can lead to sleeplessness include inconsistent bedtimes, lack of exercise, late-night employment, napping during the day, and sleep environments that include noise, lights, or screen time (National Institutes of Health 2011a).

According to the National Institute of Health, examining sleep hygiene is the first step in trying to solve a problem with sleeplessness.

For many people in the United States, however, making changes in sleep hygiene does not seem to be enough. According to a 2006 report from the Institute of Medicine, sleeplessness is an underrecognized public health problem affecting up to 70 million people. It is interesting to note that in the months (or years) after this report was released, advertising by the pharmaceutical companies behind Ambien, Lunesta, and Sepracor (three sleep aids) averaged $188 million weekly promoting these drugs (Gellene 2009).

According to a study in the American Journal of Public Health (2011), prescriptions for sleep medications increased dramatically from 1993 to 2007. While complaints of sleeplessness during doctor’s office visits more than doubled during this time, insomnia diagnoses increased more than sevenfold, from about 840,000 to 6.1 million. The authors of the study conclude that sleeplessness has been medicalized as insomnia, and that “insomnia may be a public health concern, but potential overtreatment with marginally effective, expensive medications with nontrivial side effects raises definite population health concerns” (Moloney, Konrad, and Zimmer 2011). Indeed, a study published in 2004 in the Archives of Internal Medicine shows that cognitive behavioral therapy, not medication, was the most effective sleep intervention (Jacobs, Pace-Schott, Stickgold, and Otto 2004).

A century ago, people who couldn’t sleep were told to count sheep. Now they pop a pill, and all those pills add up to a very lucrative market for the pharmaceutical industry. Is this industry behind the medicalization of sleeplessness, or is it just responding to a need?

Mental Health and Disability

The treatment received by those defined as mentally ill or disabled varies greatly from country to country. In the post-millennial United States, those of us who have never experienced such a disadvantage take for granted the rights our society guarantees for each citizen. We do not think about the relatively recent nature of the protections, unless, of course, we know someone constantly inconvenienced by the lack of accommodations or misfortune of suddenly experiencing a temporary disability.

Mental Health

People with mental disorders (a condition that makes it more difficult to cope with everyday life) and people with mental illness (a severe, lasting mental disorder that requires long-term treatment) experience a wide range of effects. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the United States has over 50 million adults with mental illness or mental disorder, or 20 percent of the total adult population. Of these, 13 million have what is considered serious mental illness or mental disorder (5 percent of the adult population); serious mental illness is that which causes impairment or disability (National Institute of Mental Health 2021). Finally, 16.5 percent of children aged 6-17 experienced mental illness or disorder (National Alliance on Mental Illness 2021).

The most common mental disorders in the United States are anxiety disorders. Almost 18 percent of U.S. adults are likely to be affected in a single year, and 28 percent are likely to be affected over the course of a lifetime (Anxiety and Depression Institute of America 2021). It is important to distinguish between occasional feelings of anxiety and a true anxiety disorder. Anxiety is a normal reaction to stress that we all feel at some point, but anxiety disorders are feelings of worry and fearfulness that last for months at a time. Anxiety disorders include obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and both social and specific phobias.

The second most common mental disorders in the United States are mood disorders; roughly 10 percent of U.S. adults are likely to be affected yearly, while 21 percent are likely to be affected over the course of a lifetime (National Institute of Mental Health 2005). Mood disorders are the most common causes of illness-related hospitalization in the U.S. (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2021). Major mood disorders are depression and dysthymic disorder. Like anxiety, depression might seem like something that everyone experiences at some point, and it is true that most people feel sad or “blue” at times in their lives. A true depressive episode, however, is more than just feeling sad for a short period. It is a long-term, debilitating illness that usually needs treatment to cure. Bipolar disorder is characterized by dramatic shifts in energy and mood, often affecting the individual’s ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. Bipolar disorder used to be called manic depression because of the way people would swing between manic and depressive episodes.

Depending on what definition is used, there is some overlap between mood disorders and personality disorders, which affect 9 percent of people in the United States yearly. A personality disorder is an enduring and inflexible pattern of long duration leading to significant distress or impairment, that is not due to use of substances or another medical condition. In other words, personality disorders cause people to behave in ways that are seen as abnormal to society but seem normal to them.

The diagnosis and classification regarding personality disorders has been evolving and is somewhat controversial. To guide diagnosis and potential treatments of mental disorders, the American Psychological Association publishes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual on Mental Disorders (DSM). Experts working on the latest version initially proposed changing the categories of personality disorders. However, the final publication retains the original ten categories, but contains an alternate/emerging approach for classifying them. This evolution demonstrates the challenges and the wide array of treating conditions, and also represents areas of difference between theorists, practitioners, governing bodies, and other stakeholders. As discussed in the Sociological Research chapter, study and investigation is a diligent and multi-dimensional process. As the diagnostic application evolves, we will see how their definitions help scholars across disciplines understand the intersection of health issues and how they are defined by social institutions and cultural norms.

Figure 19.5 Medication is a common option for children with ADHD. (Credit: Deviation56/Wikimedia Commons)

Another commonly diagnosed mental disorder is Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which affects 9 percent of U.S. children and 4 percent of adults on a lifetime basis (Danielson 2018). Since ADHD is one of the most common childhood disorders, it is often incorrectly considered only a disease found in children. But ADHD can be a serious issue for adults who either had been diagnosed as children or who are diagnosed as adults. ADHD is marked by difficulty paying attention, difficulty controlling behavior, and hyperactivity. As a result, it can lead to educational and behavioral issues in children, success issues in college, and challenges in workplace and family life. However, there is some social debate over whether such drugs are being overprescribed (American Psychological Association). A significant difficulty in diagnosis, treatment, and societal understanding of ADHD is that it changes in expression based on a wide range of factors, including age (CHADD 2020).

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) encompass a group of developmental brain disorders that are characterized by “deficits in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, and engagement in repetitive behaviors or interests” (National Institute of Mental Health). As of 2021, the CDC estimates that 1 in 54 children has an autism spectrum disorder. Beyond the very high incidence, the rate of diagnosis has been increasing steadily as awareness became more widespread. In 2005, the rate was 1 in 166 children; in 2012 it was 1 in 88 children. The rate of increase and awareness has assisted diagnosis and treatment, but autism is a cause of significant fear among parents and families. Because of its impact on relationships and especially verbal communication, children with autism (and their parents) can be shunned, grossly misunderstood, and mistreated. For example, people with an autism spectrum disorder who cannot verbalize are often assumed to be unintelligent, or are sometimes left out of conversations or activities because others feel they cannot participate. Parents may be reluctant to let their children play with or associate with children with ASD. Adults with ASD go through many of the same misconceptions and mistreatments, such as being denied opportunities or being made to feel unwelcome (Applied Behavior Analysis).

Disability

Figure 19.6 The accessibility sign indicates that people with disabilities can access the facility. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that access be provided to everyone. (Credit: Ltljltlj/Wikimedia Commons)

Disability refers to a reduction in one’s ability to perform everyday tasks. The World Health Organization makes a distinction between the various terms used to describe disabilities. They use the term impairment to describe the physical limitations, while reserving the term disability to refer to the social limitation.

Before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, people in the United States with disabilities were often excluded from opportunities and social institutions many of us take for granted. This occurred not only through employment and other kinds of discrimination but also through casual acceptance by most people in the United States of a world designed for the convenience of the able-bodied. Imagine being in a wheelchair and trying to use a sidewalk without the benefit of wheelchair-accessible curbs. Imagine as a blind person trying to access information without the widespread availability of Braille. Imagine having limited motor control and being faced with a difficult-to-grasp round door handle. Issues like these are what the ADA tries to address. Ramps on sidewalks, Braille instructions, and more accessible door levers are all accommodations to help people with disabilities.

People with disabilities can be stigmatized by their illnesses. Stigmatization means their identity is spoiled; they are labeled as different, discriminated against, and sometimes even shunned. They are labeled (as an interactionist might point out) and ascribed a master status (as a functionalist might note), becoming “the blind girl” or “the boy in the wheelchair” instead of someone afforded a full identity by society. This can be especially true for people who are disabled due to mental illness or disorders.

As discussed in the section on mental health, many mental health disorders can be debilitating and can affect a person’s ability to cope with everyday life. This can affect social status, housing, and especially employment. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2011), people with a disability had a higher rate of unemployment than people without a disability in 2010: 14.8 percent to 9.4 percent. This unemployment rate refers only to people actively looking for a job. In fact, eight out of ten people with a disability are considered “out of the labor force;” that is, they do not have jobs and are not looking for them. The combination of this population and the high unemployment rate leads to an employment-population ratio of 18.6 percent among those with disabilities. The employment-population ratio for people without disabilities was much higher, at 63.5 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2011).

SOCIOLOGY IN THE REAL WORLD

Obesity: The Last Acceptable Prejudice?

Many people who see a person with obesity may make negative assumptions about them based on their size. According to a study from the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, large people are the object of “widespread negative stereotypes that overweight and obese persons are lazy, unmotivated, lacking in self-discipline, less competent, noncompliant, and sloppy” (Puhl and Heuer 2009).

Historically, both in the United States and elsewhere, it was considered acceptable to discriminate against people based on prejudiced opinions. Even after slavery was abolished through the 13th Amendment in 1865, institutionalized racism and prejudice against Black people persisted. In an example of stereotype interchangeability, the same insults that are flung today at the overweight and obese population (lazy, for instance) have been flung at various racial and ethnic groups in earlier history.

Why is it considered acceptable to feel prejudice toward—even to hate—people with obesity? Puhl and Heuer suggest that these feelings stem from the perception that obesity is preventable through self-control, better diet, and more exercise. Highlighting this contention is the fact that studies have shown that people’s perceptions of obesity are more positive when they think the obesity was caused by non-controllable factors like biology (a thyroid condition, for instance) or genetics.

Health experts emphasize that obesity is a disease, and that it is not the result of simple overeating. There are often a number of contributing factors that make it more difficult to avoid. Even with some understanding of non-controllable factors that might affect obesity, people with obesity are still subject to stigmatization. Puhl and Heuer’s study is one of many that document discrimination at work, in the media, and even in the medical profession. Large people are less likely to get into college than thinner people, and they are less likely to succeed at work.

Stigmatization of people with obesity comes in many forms, from the seemingly benign to the potentially illegal. In movies and television shows, overweight people are often portrayed negatively, or as stock characters who are the butt of jokes. One study found that in children’s movies “obesity was equated with negative traits (evil, unattractive, unfriendly, cruel) in 64 percent of the most popular children’s videos. In 72 percent of the videos, characters with thin bodies had desirable traits, such as kindness or happiness” (Hines and Thompson 2007). In movies and television for adults, the negative portrayal is often meant to be funny. Think about the way you have seen obese people portrayed in movies and on television; now think of any other subordinate group being openly denigrated in such a way. It is difficult to find a parallel example.

Comparative Health and Medicine

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Explain the different types of health care available in the United States

- Compare the health care system of the United States with that of other countries

There are broad, structural differences among the healthcare systems of different countries. In core nations, those differences might arise in the administration of healthcare, while the care itself is similar. In peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, a lack of basic healthcare administration can be the defining feature of the system. Most countries rely on some combination of modern and traditional medicine. In core countries with large investments in technology, research, and equipment, the focus is usually on modern medicine, with traditional (also called alternative or complementary) medicine playing a secondary role. In the United States, for instance, the American Medical Association (AMA) resolved to support the incorporation of complementary and alternative medicine in medical education. In developing countries, even quickly modernizing ones like China, traditional medicine (often understood as “complementary” by the western world) may still play a larger role.

U.S. Healthcare

U.S. healthcare coverage can broadly be divided into two main categories: public healthcare (government-funded) and private healthcare (privately funded).

The two main publicly funded healthcare programs are Medicare, which provides health services to people over sixty-five years old as well as people who meet other standards for disability, and Medicaid, which provides services to people with very low incomes who meet other eligibility requirements. Other government-funded programs include service agencies focused on Native Americans (the Indian Health Service), Veterans (the Veterans Health Administration), and children (the Children’s Health Insurance Program).

Private insurance is typically categorized as either employment-based insurance or direct-purchase insurance. Employment-based insurance is health plan coverage that is provided in whole or in part by an employer or union; it can cover just the employee, or the employee and their family. Direct purchase insurance is coverage that an individual buys directly from a private company.

Even with all these options, a sizable portion of the U.S. population remains uninsured. In 2019, about 26 million people, or 8 percent of U.S. residents, had no health insurance. 2020 saw that number go up to 31 million (Keith 2020). Several more million had health insurance for part of the year (Keisler-Starkey 2020). Uninsured people are at risk of both severe illness and also chronic illnesses that develop over time. Fewer uninsured people engage in regular check-ups or preventative medicine, and rely on urgent care for a range of acute health issues.

The number of uninsured people is far lower than in previous decades. In 2013 and in many of the years preceding it, the number of uninsured people was in the 40 million range, or roughly 18 percent of the population. The Affordable Care Act, which came into full force in 2014, allowed more people to get affordable insurance. The uninsured number reached its lowest point in 2016, before beginning to climb again (Garfield 2019).

People having some insurance may mask the fact that they could be underinsured; that is, people who pay at least 10 percent of their income on healthcare costs not covered by insurance or, for low-income adults, those whose medical expenses or deductibles are at least 5 percent of their income (Schoen, Doty, Robertson, and Collins 2011).

Why are so many people uninsured or underinsured? Skyrocketing healthcare costs are part of the issue. While most people get their insurance through their employer, not all employers offer it, especially retail companies or small businesses in which many of the workers may be part time. Finally, for many years insurers could deny coverage to people with pre-existing conditions–previous illnesses or chronic diseases.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (often abbreviated ACA or nicknamed Obamacare) was a landmark change in U.S. healthcare. Passed in 2010 and fully implemented in 2014, it increased eligibility to programs like Medicaid, helped guarantee insurance coverage for people with pre-existing conditions, and established regulations to make sure that the premium funds collected by insurers and care providers go directly to medical care. It also included an individual mandate, which requires everyone to have insurance coverage by 2014 or pay a penalty. A series of provisions, including significant subsidies, are intended to address the discrepancies in income that are currently contributing to high rates of un-insurance and underinsurance. In 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate. 29 million people in the United States have gained health insurance under ACA (Economic Policy Institute 2021).

Figure 19.7 The Affordable Care Act has been a savior for some and a target for others. As Congress and various state governments sought to have it overturned with laws or to have it diminished by the courts, supporters took to the streets to express its importance to them. (Credit: Molly Adams)

The ACA remains contentious. The Supreme Court ruled in the case of National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius in 2012, that states cannot be forced to participate in the PPACA’s Medicaid expansion. This ruling opened the door to further challenges to the ACA in Congress and the Federal courts, some state governments, conservative groups and independent businesses. The ACA has been a driving factor in elections and public opinion. In 2010 and 2014, many Republican gains in Congressional seats were related to fierce concern about Obamacare. However, once millions of people were covered by the law and the economy continued to improve, public sentiment and elections swung the other way. Healthcare was the top issue for voters, and desire to preserve the law was credited for many of the Democratic gains in the election, which carried over to 2020.

Healthcare Elsewhere

Clearly, healthcare in the United States has some areas for improvement. But how does it compare to healthcare in other countries? Many people in the United States are fond of saying that this country has the best healthcare in the world, and while it is true that the United States has a higher quality of care available than many peripheral or semi-peripheral nations, it is not necessarily the “best in the world.” In a report on how U.S. healthcare compares to that of other countries, researchers found that the United States does “relatively well in some areas—such as cancer care—and less well in others—such as mortality from conditions amenable to prevention and treatment” (Docteur and Berenson 2009).

One critique of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is that it will create a system of socialized medicine, a term that for many people in the United States has negative connotations lingering from the Cold War era and earlier. Under a socialized medicine system, the government owns and runs the system. It employs the doctors, nurses, and other staff, and it owns and runs the hospitals (Klein 2009). The best example of socialized medicine is in Great Britain, where the National Health System (NHS) gives free healthcare to all its residents. And despite some U.S. citizens’ knee-jerk reaction to any healthcare changes that hint of socialism, the United States has one socialized system with the Veterans Health Administration.

It is important to distinguish between socialized medicine, in which the government owns the healthcare system, and universal healthcare, which is simply a system that guarantees healthcare coverage for everyone. Germany, Singapore, and Canada all have universal healthcare. People often look to Canada’s universal healthcare system, Medicare, as a model for the system. In Canada, healthcare is publicly funded and is administered by the separate provincial and territorial governments. However, the care itself comes from private providers. This is the main difference between universal healthcare and socialized medicine. The Canada Health Act of 1970 required that all health insurance plans must be “available to all eligible Canadian residents, comprehensive in coverage, accessible, portable among provinces, and publicly administered” (International Health Systems Canada 2010).

Heated discussions about socialization of medicine and managed-care options seem frivolous when compared with the issues of healthcare systems in developing or underdeveloped countries. In many countries, per capita income is so low, and governments are so fractured, that healthcare as we know it is virtually non-existent. Care that people in developed countries take for granted—like hospitals, healthcare workers, immunizations, antibiotics and other medications, and even sanitary water for drinking and washing—are unavailable to much of the population. Organizations like Doctors Without Borders, UNICEF, and the World Health Organization have played an important role in helping these countries get their most basic health needs met.

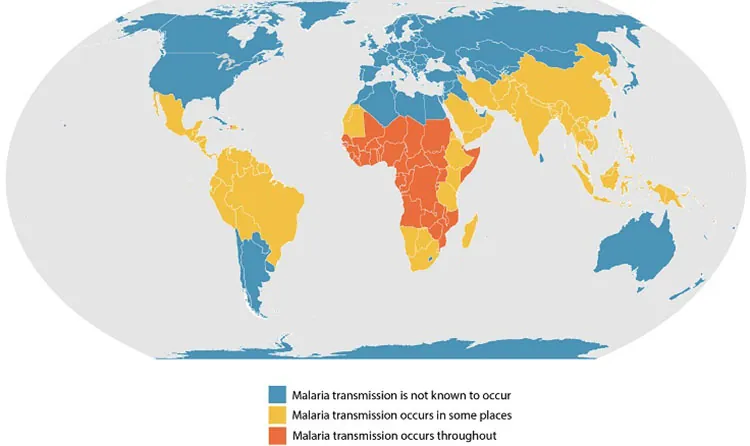

Figure 19.8 This map shows the countries where malaria is known to occur. In low-income countries, malaria is still a common cause of death. (Credit: CDC/Wikimedia Commons)

WHO, which is the health arm of the United Nations, set eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000 with the aim of reaching these goals by 2015. Some of the goals deal more broadly with the socioeconomic factors that influence health, but MDGs 4, 5, and 6 all relate specifically to large-scale health concerns, the likes of which most people in the United States will never contemplate. MDG 4 is to reduce child mortality, MDG 5 aims to improve maternal health, and MDG 6 strives to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases. The goals may not seem particularly dramatic, but the numbers behind them show how serious they are.

For MDG 4, the WHO reports that 2009 infant mortality rates in “children under 5 years old in the WHO African Region (127 per 1000 live births) and in low-income countries (117 per 1000 live births) [had dropped], but they were still higher than the 1990 global level of 89 per 1000 live births” (World Health Organization 2011). The fact that these deaths could have been avoided through appropriate medicine and clean drinking water shows the importance of healthcare.

Much progress has been made on MDG 5, with maternal deaths decreasing by 34 percent. However, almost all maternal deaths occurred in developing countries, with the African region still experiencing high numbers (World Health Organization 2011).

On MDG 6, the WHO is seeing some decreases in per capita incidence rates of malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and other diseases. However, the decreases are often offset by population increases (World Health Organization 2011). Again, the lowest-income countries, especially in the African region, experience the worst problems with disease. An important component of disease prevention and control is epidemiology, or the study of the incidence, distribution, and possible control of diseases. Fear of Ebola contamination, primarily in Western Africa but also to a smaller degree in the United States, became national news in the summer and fall of 2014.

Theoretical Perspectives on Health and Medicine

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Apply functionalist, conflict theorist, and interactionist perspectives to health issues

Each of the three major theoretical perspectives approaches the topics of health, illness, and medicine differently. You may prefer just one of the theories that follow, or you may find that combining theories and perspectives provides a fuller picture of how we experience health and wellness.

Functionalism

According to the functionalist perspective, health is vital to the stability of the society, and therefore sickness is a sanctioned form of deviance. Talcott Parsons (1951) was the first to discuss this in terms of the sick role: patterns of expectations that define appropriate behavior for the sick and for those who take care of them.

According to Parsons, the sick person has a specific role with both rights and responsibilities. To start with, the sick person has not chosen to be sick and should not be treated as responsible for her condition. The sick person also has the right of being exempt from normal social roles; they are not required to fulfill the obligation of a well person and can avoid her normal responsibilities without censure. However, this exemption is temporary and relative to the severity of the illness. The exemption also requires legitimation by a physician; that is, a physician must certify that the illness is genuine.

The responsibility of the sick person is twofold: to try to get well and to seek technically competent help from a physician. If the sick person stays ill longer than is appropriate (malingers), they may be stigmatized.

Parsons argues that since the sick are unable to fulfill their normal societal roles, their sickness weakens the society. Therefore, it is sometimes necessary for various forms of social control to bring the behavior of a sick person back in line with normal expectations. In this model of health, doctors serve as gatekeepers, deciding who is healthy and who is sick—a relationship in which the doctor has all the power. But is it appropriate to allow doctors so much power over deciding who is sick? And what about people who are sick, but are unwilling to leave their positions for any number of reasons (personal/social obligations, financial need, or lack of insurance, for instance).

Conflict Perspective

Theorists using the conflict perspective suggest that issues with the healthcare system, as with most other social problems, are rooted in capitalist society. According to conflict theorists, capitalism and the pursuit of profit lead to the commodification of health: the changing of something not generally thought of as a commodity into something that can be bought and sold in a marketplace. In this view, people with money and power—the dominant group—are the ones who make decisions about how the healthcare system will be run. They therefore ensure that they will have healthcare coverage, while simultaneously ensuring that subordinate groups stay subordinate through lack of access. This creates significant healthcare—and health—disparities between the dominant and subordinate groups.

Alongside the health disparities created by class inequalities, there are a number of health disparities created by racism, sexism, ageism, and heterosexism. When health is a commodity, the poor are more likely to experience illness caused by poor diet, to live and work in unhealthy environments, and are less likely to challenge the system. In the United States, a disproportionate number of racial minorities also have less economic power, so they bear a great deal of the burden of poor health. It is not only the poor who suffer from the conflict between dominant and subordinate groups. For many years now, same-sex couples have been denied spousal benefits, either in the form of health insurance or in terms of medical responsibility. Further adding to the issue, doctors hold a disproportionate amount of power in the doctor/patient relationship, which provides them with extensive social and economic benefits.

While conflict theorists are accurate in pointing out certain inequalities in the healthcare system, they do not give enough credit to medical advances that would not have been made without an economic structure to support and reward researchers: a structure dependent on profitability. Additionally, in their criticism of the power differential between doctor and patient, they are perhaps dismissive of the hard-won medical expertise possessed by doctors and not patients, which renders a truly egalitarian relationship more elusive.

Symbolic Interactionism

According to theorists working in this perspective, health and illness are both socially constructed. As we discussed in the beginning of the chapter, interactionists focus on the specific meanings and causes people attribute to illness. The term medicalization of deviance refers to the process that changes “bad” behavior into “sick” behavior. A related process is demedicalization, in which “sick” behavior is normalized again. Medicalization and demedicalization affect who responds to the patient, how people respond to the patient, and how people view the personal responsibility of the patient (Conrad and Schneider 1992).

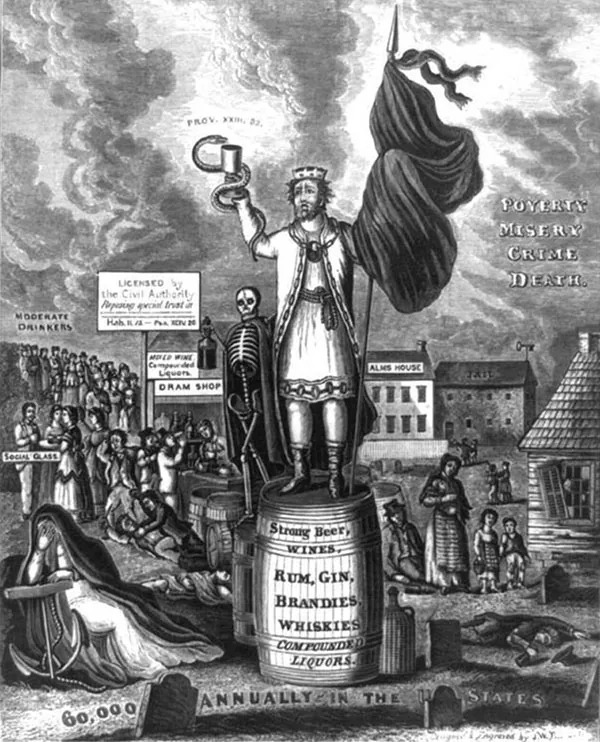

Figure 19.9 In this engraving from the nineteenth century, “King Alcohol” is shown with a skeleton on a barrel of alcohol. The words “poverty,” “misery,” “crime,” and “death” hang in the air behind him. (Credit: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

An example of medicalization is illustrated by the history of how our society views alcohol and alcoholism. During the nineteenth century, people who drank too much were considered bad, lazy people. They were called drunks, and it was not uncommon for them to be arrested or run out of a town. Drunks were not treated in a sympathetic way because, at that time, it was thought that it was their own fault that they could not stop drinking. During the latter half of the twentieth century, however, people who drank too much were increasingly defined as alcoholics: people with a disease or a genetic predisposition to addiction who were not responsible for their drinking. With alcoholism defined as a disease and not a personal choice, alcoholics came to be viewed with more compassion and understanding. Thus, “badness” was transformed into “sickness.”

There are numerous examples of demedicalization in history as well. During the Civil War era, enslaved people who escaped from their enslavers were diagnosed with a mental disorder called drapetomania. This has since been reinterpreted as a completely appropriate response to being enslaved. A more recent example is homosexuality, which was labeled a mental disorder or a sexual orientation disturbance by the American Psychological Association until 1973.

While interactionism does acknowledge the subjective nature of diagnosis, it is important to remember who most benefits when a behavior becomes defined as illness. Pharmaceutical companies make billions treating illnesses such as fatigue, insomnia, and hyperactivity that may not actually be illnesses in need of treatment, but opportunities for companies to make more money.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Social Construction of Health?

Medical sociology is the systematic study of how humans manage issues of health and illness, disease and disorders, and healthcare for both the sick and the healthy. The social construction of health explains how society shapes and is shaped by medical ideas.

Describe Global Health.

Social epidemiology is the study of the causes and distribution of diseases. From a global perspective, the health issues of high-income nations tend toward diseases like cancer as well as those that are linked to obesity, like heart disease, diabetes, and musculoskeletal disorders. Low-income nations are more likely to contend with cardiovascular disease, infectious disease, high infant mortality rates, scarce medical personnel, and inadequate water and sanitation systems.

How is Health in the United States?

Although people in the United States are generally in good health compared to less developed countries, the United States is still facing challenging issues such as a prevalence of obesity and diabetes. Moreover, people in the United States of historically disadvantaged racial groups, ethnicities, socioeconomic status, and gender experience lower levels of healthcare. Mental health and disability are health issues that are significantly impacted by social norms.

Compare between Health and Medicine

There are broad, structural differences among the healthcare systems of different countries. In core nations, those differences include publicly funded healthcare, privately funded healthcare, and combinations of both. In peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, a lack of basic healthcare administration can be the defining feature of the system.

What are Theoretical Perspectives on Health and Medicine?

While the functionalist perspective looks at how health and illness fit into a fully functioning society, the conflict perspective is concerned with how health and illness fit into the oppositional forces in society. The interactionist perspective is concerned with how social interactions construct ideas of health and illness.

References

- Book name: Introduction to Sociology 3e, aligns to the topics and objectives of many introductory sociology courses.

- Senior Contributing Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, San Jacinto College, Kathleen Holmes, Northern Essex Community College, Asha Lal Tamang, Minneapolis Community and Technical College and North Hennepin Community College.

- About OpenStax: OpenStax is part of Rice University, which is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit charitable corporation. As an educational initiative, it’s our mission to transform learning so that education works for every student. Through our partnerships with philanthropic organizations and our alliance with other educational resource companies, we’re breaking down the most common barriers to learning. Because we believe that everyone should and can have access to knowledge.

Introduction

- ABC News Health News. “Ebola in America, Timeline of a Deadly Virus.” Retrieved Oct. 23rd, 2014 (http://abcnews.go.com/Health/ebola-america-timeline/story?id=26159719).

- Centers for Disease Control. 2011b. “Pertussis.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 15, 2011 (http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks.html).

- Centers for Disease Control. 2020. “What Is Ebola Virus Disease.” (https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/about.html)

- Conrad, Peter, and Kristin Barker. 2010. “The Social Construction of Illness: Key Insights and Policy Implications.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51:67–79.

- CNN. 2011. “Retracted Autism Study an ‘Elaborate Fraud,’ British Journal Finds.” CNN, January 5. Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://www.cnn.com/2011/HEALTH/01/05/autism.vaccines/index.html).

- Devlin, Kate. 2008. “Measles worry MMR as vaccination rates stall.” The Telegraph, September 24. Retrieved January 19, 2012 (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/3074023/Measles-worries-as-MMR-vaccination-rates-stall.html).

- Sugerman, David E., Albert E. Barskey, Maryann G. Delea, Ismael R. Ortega-Sanchez, Daoling Bi, Kimberly J. Ralston, Paul A. Rota, Karen Waters-Montijo, and Charles W. LeBaron. 2010. “Measles Outbreak in a Highly Vaccinated Population, San Diego, 2008: Role of the Intentionally Undervaccinated.” Pediatrics 125(4):747–755. Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://www.pediatricsdigest.mobi/content/125/4/747.full).

- World Health Organization. 2014. “Global Alert and Response.” Retrieved Oct. 23rd 2014 (http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/en/).

- Zacharyczuk, Colleen. 2011. “Myriad causes contributed to California pertussis outbreak.” Thorofar, NJ: Pediatric Supersite. Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://www.pediatricsupersite.com/view.aspx?rid=90516).

19.1 The Social Construction of Health

- Begos, Kevin. 2011. “Pinkwashing For Breast Cancer Awareness Questioned.” Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/10/11/breast-cancer-pink-pinkwashing_n_1005906.html).

- Centers for Disease Control. 2011a. “Perceived Exertion (Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/measuring/exertion.html).

- Conrad, Peter, and Kristin Barker. 2010. “The Social Construction of Illness: Key Insights and Policy Implications.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51:67–79.

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin.

- Hutchison, Courtney. 2010. “Fried Chicken for the Cure?” ABC News Medical Unit. Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://abcnews.go.com/Health/Wellness/kfc-fights-breast-cancer-fried-chicken/story?id=10458830#.Tutz63ryT4s).

- Sartorius, Norman. 2007. “Stigmatized Illness and Health Care.” The Croatian Medical Journal 48(3):396–397. Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2080544/).

- Think Before You Pink. 2012. “Before You Buy Pink.” Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://thinkbeforeyoupink.org/?page_id=13).

- “Vaccines and Immunizations.” 2011. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/default.htm).

- World Health Organization. .n.d. “Definition of Health.” Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html).

- World Health Organization: “Health Promotion Glossary Update.” Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/about/HPR%20Glossary_New%20Terms.pdf).

19.2 Global Health

- Bromet et al. 2011. “Cross-National Epidemiology of DSM-IV Major Depressive Episode.” BMC Medicine 9:90. Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/90).

- Dagenais, Gilles and Darryl P Leong, PhD and Sumathy Rangarajan, MSc and Fernando Lanas, PhD and Prof Patricio Lopez-Jaramillo, PhD and Prof Rajeev Gupta, PhD. 2019. “Variations in common diseases, hospital admissions, and deaths in middle-aged adults in 21 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study.” September 8 2019. (https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32007-0/fulltext#articleInformation)

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020

- Huffman, Wallace E., Sonya Kostova Huffman, AbebayehuTegene, and KyrreRickertsen. 2006. “The Economics of Obesity-Related Mortality among High Income Countries” International Association of Agricultural Economists. Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://purl.umn.edu/25567).

- Mahase, Elisabeth. 2019. “Cancer overtakes CVD to become leading cause of death in high income countries” The BMJ. September 3 2019. (https://www.bmj.com/content/366/bmj.l5368)

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2011. Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2011-en).

- UNICEF. 2011. “Water, Sanitation and Hygiene.” Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://www.unicef.org/wash).

- World Health Organization. 2011. “World Health Statistics 2011.” Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2011_Part1.pdf).

19.3 Health in the United States

- Agency for Health Research and Quality. 2010. “Disparities in Healthcare Quality Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups.” Agency for Health Research and Quality. Retrieved December 13, 2011 (http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhqrdr10/nhqrdrminority10.htm)

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2021 “HCUP Fast Stats. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). March 2021. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/national/inpatientcommondiagnoses.jsp?year1=2017)

- Agency for HealthCare Research and Quality. 2020. “2019 National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Report.” (https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/2019qdr-intro-methods.pdf)

- American Psychological Association. 2011a. “A 09 Autism Spectrum Disorder.” American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Development. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- American Psychological Association. 2011b. “Personality Traits.” American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Development. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- American Psychological Association. n.d. “Understanding the Ritalin Debate.” American Psychological Association. Retrieved December 14, 2011 (http://www.apa.org/topics/adhd/ritalin-debate.aspx)

- Anxiety and Depression Institute of America. 2021. “Facts and Statistics.” Retrieved April 1 2021. (https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/facts-statistics)

- Applied Behavior Analysis. “30 Things Parents of Children on the Autism Spectrum Want You to Know” (https://www.appliedbehavioranalysisprograms.com/things-parents-of-children-on-the-autism-spectrum-want-you-to-know/)

- Becker, Dana. n.d. “Borderline Personality Disorder: The Disparagement of Women through Diagnosis.” Retrieved December 13, 2011 (http://www.awpsych.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=109&catid=74&Itemid=126).

- Berkman, Lisa F. 2009. “Social Epidemiology: Social Determinants of Health in the United States: Are We Losing Ground?” Annual Review of Public Health 30:27–40.

- Blumenthal, David, and Sarah R. Collins. 2014 “Health Care Coverage under the Affordable Care Act—a Progress Report.” New England Journal of Medicine 371 (3): 275–81. Retrieved December 16, 2014 (https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/717/04/).

- Centers for Disease Control. 2021. “Infant Mortality.” (https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm)

- CHADD. 2021. “ADHD Changes in Adulthood.” Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. (https://chadd.org/adhd-weekly/adhd-changes-in-adulthood/)

- Danielson, Melissa L. Rebecca H. Bitsko, Reem M. Ghandour, Joseph R. Holbrook, Michael D. Kogan & Stephen J. Blumberg. 2018. “Prevalence of Parent-Reported ADHD Diagnosis and Associated Treatment Among U.S. Children and Adolescents, 2016.” Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47:2, 199-212, DOI: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860

- Fox, B., and D. Worts. 1999. “Revisiting the Critique of Medicalized Childbirth: A Contribution to the Sociology of Birth.” Gender and Society 13(3):326–346.

- Gellene, Denise. 2009. “Sleeping Pill Use Grows as Economy Keeps People up at Night.” Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://articles.latimes.com/2009/mar/30/health/he-sleep30).

- Hines, Susan M., and Kevin J. Thompson. 2007. “Fat Stigmatization in Television Shows and Movies: A Content Analysis.” Obesity 15:712–718. Retrieved December 15, 2011 (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1038/oby.2007.635/full).

- Institute of Medicine. 2006. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

- Jacobs, Gregg D., Edward F. Pace-Schott, Robert Stickgold, and Michael W. Otto. 2004. “Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Pharmacotherapy for Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial and Direct Comparison.” Archives of Internal Medicine 164(17):1888–1896. Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=217394).

- James, Cara et al. 2007. “Key Facts: Race, Ethnicity & Medical Care.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved December 13, 2011 (http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/upload/6069-02.pdf).

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2018. “Key Findings From the Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. March 13 2018. (https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/child-mortality)

- Keck School of Medicine. 2020. “The Shrinking Child Mortality Rate: 5 Things to Know.” Keck School of Medicine of University of Southern California. (https://mphdegree.usc.edu/blog/the-shrinking-child-mortality-rate-5-things-to-know/)

- Moloney, Mairead Eastin, Thomas R. Konrad, and Catherine R. Zimmer. 2011. “The Medicalization of Sleeplessness: A Public Health Concern.” American Journal of Public Health 101:1429–1433.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. 2021. “Mental Health By The Numbers.” Retrieved April 1, 2021. (https://www.nami.org/mhstats)

- National Institute of Mental Health. 2005. “National Institute of Mental Health Statistics.” Retrieved December 14, 2011 (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/index.shtml).

- National Institutes of Health. 2011a. “Insomnia.” The National Institute of Health. Retrieved December 16, 2011 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001808/).

- National Institutes of Health. 2011b. “What is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)?” National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved December 14, 2011 (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/a-parents-guide-to-autism-spectrum-disorder/what-is-autism-spectrum-disorder-asd.shtml).

- National Institute of Mental Health. 2021. “Mental Illness.” Retrieved April 1, 2021. (https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml#part_15)

- Phelan, Jo C., and Bruce G. Link. 2001. “Conceptualizing Stigma” Annual Review of Sociology 27:363–85. Retrieved December 13, 2011 (http://www.heart-intl.net/HEART/Legal/Comp/ConceptualizingStigma.pdf).

- Phelan, Jo C., and Bruce G. Link. 2003. “When Income Affects Outcome: Socioeconomic Status and Health.” Research in Profile: 6. Retrieved December 13, 2011 (http://www.investigatorawards.org/downloads/research_in_profiles_iss06_feb2003.pdf).

- Puhl, Rebecca M., and Chelsea A. Heuer. 2009. “The Stigma of Obesity: A Review and Update.” Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved December 15, 2011 (http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/upload/docs/what/bias/WeightBiasStudy.pdf).

- Ranji, Usha, and Alina Salganico. 2011. “Women’s Health Care Chartbook: Key Findings from the Kaiser Women’s Health Survey.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved December 13, 2011 (http://www.kff.org/womenshealth/upload/8164.pdf=).

- Scheff, Thomas. 1963. Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Szasz, Thomas. 1961. The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2011. “Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012.” 131st ed. Washington, DC. Retrieved December 13, 2011 (http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2011. “Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics News Release.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved December 14, 2011 (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/disabl.htm).

- Wamsley, Laurel. 2021. “American Life Expectancy Dropped by a Full Year in the 1st Half of 2020.” National Public Radio. February 18 2021. (https://www.npr.org/2021/02/18/968791431/american-life-expectancy-dropped-by-a-full-year-in-the-first-half-of-2020)

- Winkleby, Marilyn A., D. E. Jatulis, E. Frank, and S. P. Fortmann. 1992. “Socioeconomic Status and Health: How Education, Income, and Occupation Contribute to Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease.” American Journal of Public Health 82:6.

- World Health Organization. 2020. “Children: Improving Survival and Well-Being.” September 8 2020. (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/children-reducing-mortality)

- World Health Organization. 2021. “Child Mortality.” Retrieved April 1 2020. (https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/child-mortality)

19.4 Comparative Health and Medicine

- Anders, George. 1996. Health Against Wealth: HMOs and the Breakdown of Medical Trust. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 “Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Data and Statistics.” Retrieved October 13, 2014 (http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html)

- Docteur, Elizabeth, and Robert A. Berenson. 2009. “How Does the Quality of U.S. Health Care Compare Internationally?” Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues 9:1–14.

- Economic Policy Institute. 2021. “How would repealing the ACA affect healthcare and jobs in your state?” (https://www.epi.org/aca-obamacare-repeal-impact/)